In 2013, Microsoft made a bold move by acquiring Nokia’s phone business for $7.2 billion.

During a press conference about the merger, Nokia’s CEO Stephen Elop ended his speech with the words,

“We didn’t do anything wrong, but somehow, we lost.”

In saying this, he seemed to acknowledge that the company had failed to adapt to the evolving marketplace.

The deal was expected to bolster Microsoft’s presence in the mobile market, leveraging Nokia’s hardware prowess and Microsoft’s software expertise.

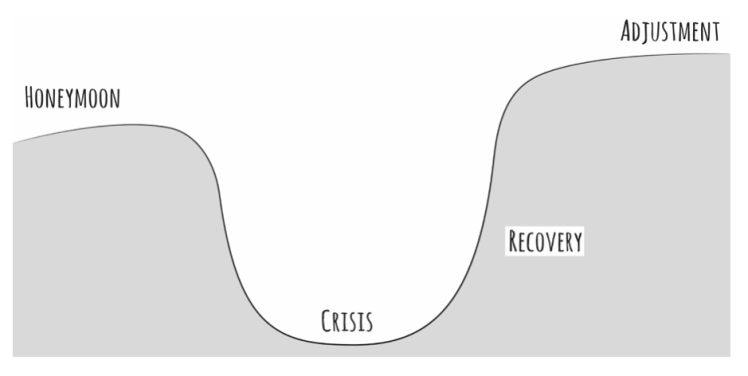

However, unlike Geely’s acquisition of Volvo, the integration of the two companies soon revealed significant challenges, particularly in managing the cultural differences between employees from the Finnish and American firms.

Background of the Deal

The acquisition was strategic: Nokia had a strong global presence in the mobile phone market, and Microsoft needed to strengthen its position against competitors like Apple and Google.

The merger aimed to create a seamless hardware-software ecosystem that would rival the market leaders.

But the rub came when integrating Nokia’s employees into Microsoft’s corporate culture.

Cultural Clashes and Communication Barriers

The corporate cultures of the two companies were night and day.

Nokia, a Finnish company, had a more egalitarian and consensus-driven approach to decision-making.

Finnish employees valued autonomy, modesty, and a non-hierarchical work environment.

In contrast, Microsoft’s culture was more top-down, with a focus on individual performance and aggressive competition.

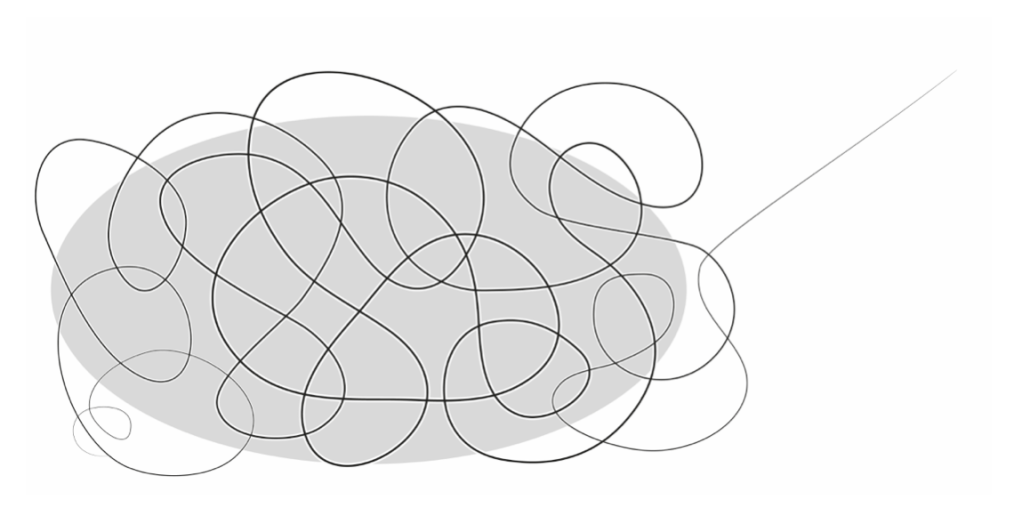

These differences led to significant communication barriers.

Finnish employees felt overwhelmed by Microsoft’s assertive communication style, which they perceived as abrasive and confrontational.

On the other hand, Microsoft employees found Nokia’s approach too passive and slow, leading to frustration and misunderstandings.

Integration and Trust Issues

Building trust between the two groups was another major hurdle.

Many Nokia employees were skeptical about Microsoft’s intentions and feared job losses.

This anxiety was not unfounded, as Microsoft announced significant layoffs shortly after the acquisition, further straining relations and diminishing morale.

Efforts to unify the teams often fell short due to these underlying tensions.

Microsoft attempted to impose its processes and practices on Nokia, which led to resistance and disengagement from Finnish employees who felt their expertise and methods were undervalued.

Strategic Misalignments

Beyond cultural integration, there were also strategic misalignments.

Nokia had been focused on producing hardware, while Microsoft’s expertise lay in software.

Bridging this gap required not just cultural integration but also a harmonization of business strategies.

Unfortunately, these efforts were hampered by the ongoing cultural friction, leading to delays and suboptimal product development.

A Failed Experiment: Lessons Learned

The Microsoft-Nokia acquisition serves as a cautionary tale about the complexities of cross-cultural integration.

It underscores the importance of cultural due diligence in mergers and acquisitions.

It’s not enough to align business goals; companies must also consider the cultural compatibility of their workforces.

Effective communication, mutual respect, and a willingness to adapt are crucial for successful integration.

To mitigate such issues, companies can implement cross-cultural training programs, establish clear communication channels, and promote a culture of inclusivity and collaboration.

By valuing and integrating diverse perspectives, organizations can turn cultural differences into strengths rather than obstacles.

While the deal had strong strategic merits, the failure to effectively manage cultural differences ultimately undercut the intended synergies.