Who do you trust? And why?

The answer may be partially rooted in your culture.

Through two eye-opening experiments in a study on cross-cultural differences in trust, researchers examined how people from different cultures build trust with strangers.

They focused on Americans and Japanese, expecting their trust-building methods to differ.

And they were right.

American vs. Japanese Trust

For Americans, trust was thought to come from shared group memberships, while for Japanese, it was about having direct or indirect connections with others.

The results confirmed these ideas.

In both experiments – one involving questions and the other a money-sharing game – Americans trusted people from their in-group more.

But for the Japanese, something interesting happened: when there was a chance of having an indirect connection with someone outside their group, their trust increased even more than for Americans.

These findings show how cultural backgrounds shape the way we trust others.

For Americans, it’s about being part of the same group, while for Japanese, it’s more about having connections, even if they’re not direct.

Understanding these differences is crucial for better communication and relationships across cultures.

And for negotiations.

Understanding the Significance of Trust

In cross-cultural negotiations, trust goes beyond mere reliance on promises or assurances; it reflects a deep-seated belief in the integrity, credibility, and goodwill of one’s counterparts.

Trust fosters open communication, facilitates collaboration, and enhances the likelihood of reaching mutually satisfactory outcomes.

Without trust, negotiations may stall, misunderstandings may arise, and relationships may falter.

Strategies for Building Trust Across Cultural Divides

Think about what you learned in the earlier study.

Before negotiations commence, you might consider researching how the culture views trust and attempting to adapt to that view.

For instance, let’s say you’re a businessperson from the United States negotiating a deal with a company based in Japan.

In American culture, trust might be primarily based on shared goals or business interests.

However, in Japanese culture, trust is often built through personal connections and relationships.

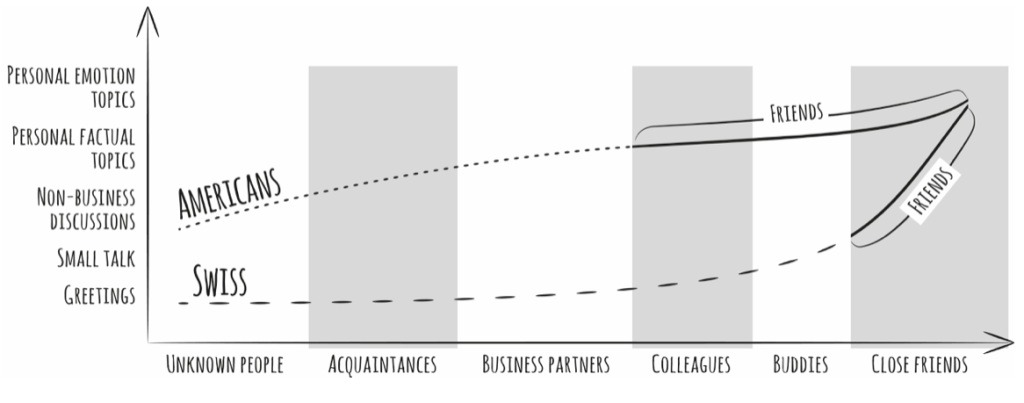

To adapt to the Japanese cultural sense of trust, you might prioritize building rapport and establishing personal connections before diving into business discussions.

This could involve taking the time to engage in small talk, showing genuine interest in your Japanese counterparts’ backgrounds and interests, and demonstrating respect for their cultural norms and customs.

By understanding and adapting to the Japanese view of trust, you can lay the foundation for a more productive and harmonious negotiation process, ultimately increasing the likelihood of reaching a mutually beneficial agreement.

We’ll discuss more strategies for building trust next week.