You expect coming home to be euphoric.

And it is…for a minute.

But after that minute is over, in euphoria’s place is a feeling of unease, discomfort, and even sadness.

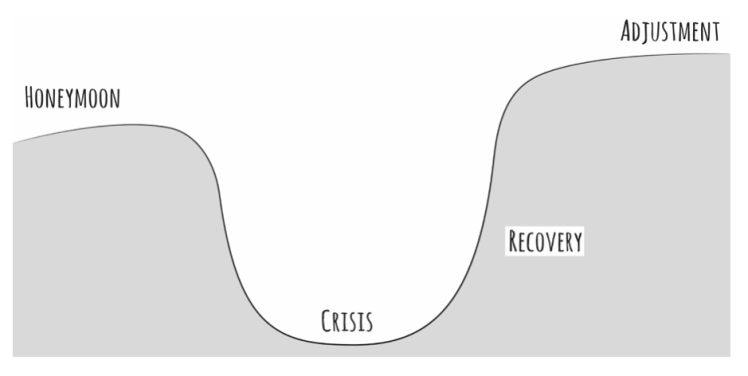

What you’re feeling is reverse culture shock, and it’s even stronger than the culture shock you experienced in your home country.

As described by the Founder of DFA Intercultural Global Solutions Dean Foster on expatica:

“[Reverse culture shock] is far more subtle, and therefore, more difficult to manage than outbound shock precisely because it is unexpected and unanticipated.”

Foster explains that the “patterns of behavior and thought” that an expat has developed to fit into his or her host country have now become part of them.

The change is gradual and not necessarily always conscious.

So, upon returning home, the expat is shocked to find the changes within themselves.

Their home culture may have changed as well. It can seem a bit off, making it appear uncanny or surreal, like a funhouse mirror.

Readjusting to both the changes within oneself and within one’s home culture can feel like a double-whammy.

Another Thing: No One Cares…

What’s more, as an expat, you’re often excited and bursting to share your experience abroad, particularly if this was your first experience.

You are expecting a curious audience of family and friends awaiting your arrival.

You have great expectations.

But what you more often find is that no one cares.

Your family and friends have been living their own lives while you’ve been off living yours.

They are wrapped up in the day-to-day back home; not so much concerned with the many “monkey moments” you had in a world they’ve never visited.

You may get an odd question here or there out of courtesy – not much more than an open-ended “so, how was it?” or a “did you have a good time?” – but no one is sitting on the edge of their seat, waiting attentively for your tale of life abroad.

All of this might make you feel a number of things: annoyed with your family and friends, alienated from your home country, and homesick for your host country.

Your relationships may have changed back home too, having lost out on some experiences (weddings, births, or other family/friend events, for instance) while you were away.

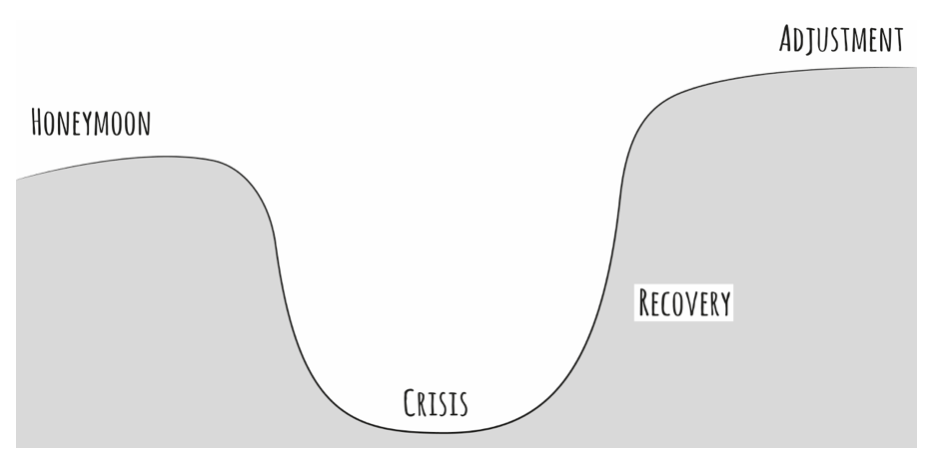

What can you do to reduce the shock of all these changes and feelings?

Find Your People

One, you can find your people.

Other expats who are experiencing the same reverse culture shock as you often hold support groups either online or in person in major cities. You don’t even have to be from the same host country; you have a shared experience of returning from a foreign land and feeling these same effects.

Moreover, those with this shared experience are more likely to be that rapt audience you were searching for. Curiosity about the world is built-in, so you’ll be able to share your experiences and swap stories about life abroad without feeling like your audience is uninterested or disconnected.

As for homesickness, you might find ways to embrace your change in personality and continue in the lifestyle you’ve developed abroad at home.

Cook up some of your favorite meals from your host country, continue with your language lessons, stay connected to your host country friends – keep in touch this other part of who you are.

You’ve enriched your life with this experience abroad, and even though you may not be encouraged to unload your memoir on everyone in your life, you should nurture it and let it continue to be a quiet new branch of your personal baobab.