Rules or relationships.

Where is the emphasis placed in your culture? Which is valued more?

Identifying where your values lie will tell you whether you’ve grown up in a relationship-based culture or a rule-based culture.

Once you discover what grounds you, you may wonder how these values impact the mechanics of your culture and your own decision-making and moral perspective.

Let’s take a look.

A Query in Context

I recently received an email query about rule-based versus relationship-based cultures.

The anonymous author wrote:

“I’m a lawyer in the USA, and I tend to be more black/white and rule-based. I’ve encountered attorneys and judges that don’t seem to care about the rules (aka the law) and it can be frustrating…

When I think about it, how can the law have any place in a society that is not rule-based? Your example of lying to protect your friend from criminal prosecution for killing someone in a school zone by speeding in a relationship-based society flaunts the law. It supports the whims of men, which may change from time to time much faster than the law. It destroys expectations…

How can I plan for the future when some bureaucrat may decide the law doesn’t apply to my adversary, contract counterparty, tortfeasor, etc? It supports dishonesty and bribery, as is common, at least more overtly, in the rest of the world.

What about judicial and lawyer ethics codes? How can those matter if you live in a non-rule-based society? It’s OK that I lied to the court to protect my client/brother? Really? That can’t be ‘right.’ Moral relativism must have a stopping point…”

Let’s see if we can clear a few of these questions up.

Rule of Law in Culture

The post anonymous is referring to is Rule of Law in Culture: Are Laws More Important Than Relationships?

It describes a study in which U.S. and Venezuelan managers were surveyed about the hypothetical scenario described.

U.S. participants more heavily leaned toward testifying against their friend who broke the law, while two thirds of Venezuelan managers said they would lie in their testimony to cover for the friend.

The scenario illustrates where each cultures values lie.

But just because a culture prioritizes relationships over rules does not mean the rules don’t exist or apply.

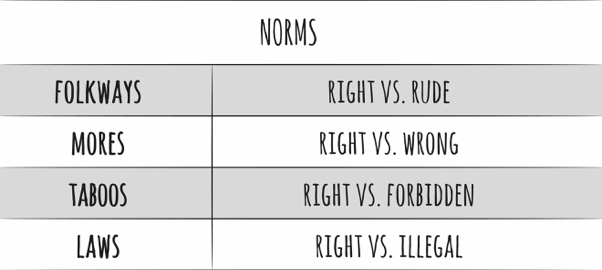

All societies have rules. Sometimes those rules are relationship-based, as described in my post, Relationship- vs. Rule-Based Cultures: Socially-Based Control vs. Individual Autonomy.

The post illustrates how the Shona society is ruled by a hierarchy based on familial relationships. It’s a fundamental part of their culture.

Unlike some cultures, where laws strive to be objective, the laws of the Shona society are shaped by relationships. Still, the rules exist.

This is just one example, but perhaps the misunderstanding is in what these two terms mean.

What “Rule-based” and “Relationship-based” Truly Means

Do the terms “rule-based” and “relationship-based” imply there are no rules (and no application of these rules) in the latter and no relationships in the former?

No.

It’s a matter of priority – i.e. do you break rules because of relations, or do you stick to rules, despite harming your relationships?

In rule-based cultures, an individual’s priority is, more often than not, on the law, while in relationship-based cultures, relationships take priority.

This does not mean there is no place for rule of law in relationship-based cultures. In regard to the study example, it wasn’t that the law or the legal system, the lawyer or the judge, was prioritizing relationships; it was the witness – an individual in the relationship-based society – prioritizing them.

The example about lying to protect your friend from criminal prosecution was not to indicate whether doing so is “right” or “wrong.” As we’ve also discussed in this blog, one culture’s “right” is always another one’s “wrong,” and such ideologies are shaped by primary socialization.

Anonymous questions this, writing, “Moral relativism must have a stopping point.”

In other posts, we’ve described this stopping point. We’ve outlined what active tolerance is, how to accept conflicting cultural values, and when to personally arrive at this “stopping point” when working cross-culturally.

You might choose to draw the line of moral relativism at harm, as described in our post: “tolerance ends where harm begins.”

In this instance, your stopping point might be that your friend should be in prison. Or it might be that your friend’s life and your shared relationship is more important.

Whether or not valuing relationships over rules “flaunts the law” or is unethical is both for the society to decide and for you – on a personal level – to decide.

Prioritizing Relationships Over Rules

In a cross-cultural sense, understanding the rationale behind another culture’s priorities is the best you can do to make that decision for yourself and know where you draw the line.

To see the logic, you must empathize and understand the mechanics of the culture, which are based on the values it upholds.

Once you achieve that understanding, it’s easy to see why those who value relationships might wish to support the relationship over the law.

“Cultural Differences in Business Communication,” by John Hooker, describes exactly why one’s priority might lie with the relationship:

“In relationship-based cultures, the unit of human existence is larger than the individual, perhaps encompassing the extended family or the village. Ostracism from the group is almost a form of death, because one does not exist apart from one’s relatedness to others.”

If you’re part of a clock, do you remove the minute hand?

No.

Just as every part in a clock has a relationship to the other parts, so do the people in a relationship-based society.

When destroying that relationship means death, you’d agree that even the law is less important.

As with Victor Hugo’s Les Miserable, the concept of flaunting the law – stealing bread rather than letting your family starve to death – brings that idea to the fore.

What would you do? Is what you’d do “right” or “wrong”? And how does your choice reflect your values?

Prioritizing Rules Over Relationships

And, in the other vein, you can understand why those cultures who value rules might stand by the law instead of the relationship.

Rule-based cultures are usually individualist and don’t have the same level of relationship connectedness as collectivist, relationship-based cultures.

Because of this, the mechanics of the society don’t work the same.

You might remove and replace the minute hand of the clock, because it kept getting stuck.

Just as you might testify as a witness against your speeding friend, as you believe him to be a danger to society.

More importantly, your rule-based society won’t ostracize you for telling the truth, because most view justice in the same way as you do; in fact, you’ll likely even be praised for putting the rule of law over your relationship, as this is a difficult decision to face.

In both societies, rules exist. But the individual chooses where to place their loyalty, which is all based on cultural conditioning and the reciprocal relationships between individuals in a culture.

Whether or not anonymous (or anyone in a rule-based society) believes putting relationships over rules is unjustified or unethical, this doesn’t necessarily mean doing so is “wrong” or there isn’t logic and reason in such societies.

What is the Point of Law?

Anonymous ends with the question,

“So what is the point of law and lawyers in non-rule-based societies? How does it work? Is it more about manipulation, sales, and gamesmanship than seeking objective truth?”

There are benefits and costs to both types of governance.

John Shuhe Li’s article, entitled “The Benefits and Costs of Relation-based Governance: An Explanation of the East Asian Miracle and Crisis,” provides some examples of these costs/benefits.

Li first emphasizes that agreements can only be enforced through rules or relationships. If neither exist, governance resorts to violence.

Li then outlines the benefits of relationship-based governance compared to rule-based governance, writing:

“When relation-based governance works, given two transaction partners, it can enforce all mutually observable agreements (by the two parties). When one party deviates from a mutually observable agreement, the other party can punish the deviator by playing (for example) tit-for-tat strategies. In contrast, given two transaction partners, rule-based governance can only enforce a subset of the mutually observable agreements that can also be observed by third parties. Thus, perhaps a large part of monitored-activities, which are mutually observable by the monitor and the monitee but are not verifiable by a third party can be enforced by relation-based governance, but not by rule-based governance.”

He also describes how a small relationship-based market can lower transaction costs over the larger fixed cost in a rule-based market. There are some limitations in this, however, including the small number of partners one can force relations agreements with.

Rule-based governance has its benefits, as well.

Li writes,

“In contrast, there exist economies of scale in rule-based governance; thus a firm can resort to rule-based governance to enforce contracts (impersonal agreements) with an unlimited number of partners, including strangers.”

The activity coordination of the transaction parties can result in the sharing of more technical information (information not directly related to enforcement) in relation-based governance, which is another advantage. Moreover, without all the bureaucracy, renegotiations in relation-based governance can be less costly.

Lastly, when it comes to business, the fact remains that some economies are catching-up economies and can’t rely on rule-based governance.

Li writes,

“In catching-up economies…relation-based governance is the only available mechanism to enforce agreements. Thus, investing in relations can be profitable and rational, especially in developing countries.”

While this refers to business rather than criminal law, you can see that there is a point of law and lawyers in relationship-based societies; the rules simply lean more heavily into relying on relationships to enforce the rules of an agreement and keeping relationships on good terms.

And across cultures, those terms vary.