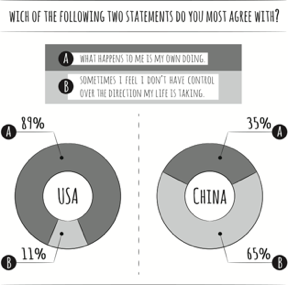

The degree to which a person believes in destiny is largely formed by their culture.

It can also be influenced by location, gender, ethnicity, and many other factors that impact a person’s primary socialization and conditioning.

Last week, we discussed the role culture plays in the locus of control.

This week, we’ll continue that discussion, fleshing out the roles location and gender have in a person’s sense of control over his/her own life.

Location, Location, Location

In John H. Sims and Duane D. Baumann’s study, “The Tornado Threat: Coping Styles of the North and South,” a survey was taken across two U.S. states: the state of Illinois and the state of Alabama.

The objective of the survey was to identify why these two states reacted differently in preparing for natural disasters, specifically tornadoes.

Alabama often has an alarmingly higher number of fatalities (23 in 2019, for example) than Illinois (0 in 2019).

One factor that may be contributing to that difference in coping with tornadoes is the locus of control.

After surveying four counties, a majority of Alabama residents demonstrated an external locus, while a majority of Illinois residents demonstrated an internal locus.

Considering the locus of control dictates to what degree a person/group feels they have control over their own fate, the line of logic suggests that preparation for natural disasters would differ across these two states according to the group’s collective locus.

More precautions would be taken by Illinois residents whose internal locus of control would make them proactive in reacting to tornado warnings, as they believe they have control over the outcome, while residents of Alabama, with their external locus of control, are more prone to leaving fate up to the whims of nature.

The conclusion, then, is that a region’s collective locus of control can influence the number of fatalities caused by natural disasters – and likely influence many other things related to our sense of control or lack thereof.

Gender

Gender also comes into play in regards to one’s locus of control.

One example of this can be found in M. A. Hamedoglu’s “The Effect of Locus of Control and Culture on Leader Preferences.”

In testing undergraduate students from Western and Eastern cultures, this study found that men are more often of an external locus of control, giving preference to autocratic leadership styles, while women are geared more toward an internal locus of control, preferring democratic leadership styles.

This collective locus regarding gender can impact everything from leadership preference to conflict resolution to one’s sense of accountability.

Next week, we’ll talk about how individuals across cultures try to control their fate, whether their locus of control is external or internal.