Ever driven by a sign that says your city is “sisters” with some far-flung place like Timbuktu and thought to yourself, “Really? How did that happen?”

Well, in the US, it’s a tale as old as…1956.

While we covered how Sister Cities were born out of World War II, the US program was launched by President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s “People-to-People” conference in 1956.

Ike, clearly ahead of his time, envisioned world peace not through big speeches or flashy treaties, but through ordinary people connecting across borders.

Thus, Sister Cities International (SCI) was created, a nonprofit that has since grown to link over 500 US cities with more than 2,100 global counterparts.

It’s like an international club but with trade delegations, cultural festivals, and sometimes awkward exchanges of ceremonial plaques.

Sister Cities in the Best of Times

You might be wondering, “What do Sister Cities actually do?

Great question.

These partnerships aren’t just symbolic – they’re active, and they make a real impact.

Each Sister City relationship is unique, but here are the four main flavors of collaboration:

1. Arts and Culture

Exchanging cultural expression – such as music, art, or festivals – is a cornerstone of Sister Cities.

Communities share in each other’s traditions, encouraging appreciation of other cultures.

2. Business and Trade

Economic collaboration between Sister Cities facilitates everything from business exchanges to trade missions.

The aim is to grow both regions by tapping into each other’s economic strengths and resources.

3. Community Development

Sister cities are all about problem-solving.

They look toward innovative solutions to issues like healthcare and sustainability.

Providing the other with expertise, resources, or support, Sister Cities find solutions to each other’s problems – just like any sister would.

4. Youth and Education

Youth programs and educational exchanges contribute to the energy of Sister City relationships.

These initiatives give young people the chance to learn about other cultures, develop leadership skills, and build international friendships on the other side of the world.

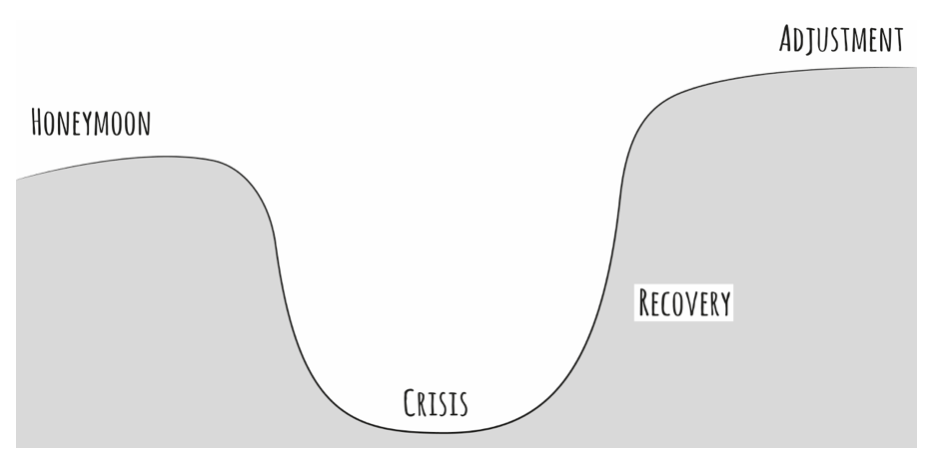

Sister Cities in the Worst of Times

If 2020 taught us anything, it’s that in the worst of times, people find ways to step up – even across international borders.

Sister Cities provided aid in crisis. And they played a quiet but impactful role during a year that tested everyone.

When wildfires ravaged Oregon, firefighters from Guanajuato, Mexico, flew to their Sister City, Ashland, to lend a hand.

Firefighters from Querétaro did the same for Bakersfield, California.

And during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, the concept of “mask diplomacy” came to life.

Hanam City, South Korea, sent masks to Little Rock, Arkansas; Naka, Japan, supported Oak Ridge, Tennessee; and cities in China, like Harbin and Changsha, provided aid to Anchorage, Alaska, and Annapolis, Maryland.

This wasn’t a one-way street.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, donated masks to Wuhan, China, at the pandemic’s onset, and Phoenix, Arizona, funded a new kindergarten for Chengdu, China, after the devastating 2008 earthquake.

These actions underscore the unique ability of Sister Cities to foster goodwill and humanitarian support, even when national-level relationships are strained.

The Eisenhower Effect

When Eisenhower pitched this idea, he probably didn’t imagine mayors swapping hats or communities hosting dumpling-making contests…or the pandemic.

But that’s the beauty of Sister Cities – they’re living proof that diplomacy can be done with a smile.

In a world that sometimes feels more divided than ever, these partnerships remind us that peace doesn’t have to come in the form of grand gestures.

Sometimes, it’s just about showing up. One city, one connection, one laughably oversized welcome sign at a time.